Human life is full of rituals, practices, and liturgies. Whether religious or irreligious, these things form us into certain kinds of people. Perhaps we would not use these exact terms, but the realities represented by them are inescapable. Many people cannot fathom the idea of Christmas without decorating a Christmas tree or hanging a stocking above the fireplace. While Christians may often debate whether it’s right or wrong to perform individual acts, it is also important that we look at how the repetition of certain traditions over a period of years reinforces implicit assumptions about what ultimately matters. In this article, I want to suggest that how you celebrate Christmas has a role in shaping whom you and your family will become.

Let me begin by briefly defining the three terms used above.* The word ritual, as I’m using it here, refers loosely to personal habits that are not always performed consciously and that do not necessarily have any great goal in mind. A practice is a step beyond a ritual. A practice is a habit that is often consciously done, and for a specific goal. Lastly, a liturgy is a practice or set of practices that ought to be consciously done, and not just done for any goal, but for the ultimate goal of life, which for the Christian is the worship of God. As an exercise in application, ask yourself these questions, “Which of these three categories does my experience of Christmas best fit into? Which should it fit into, and why?”

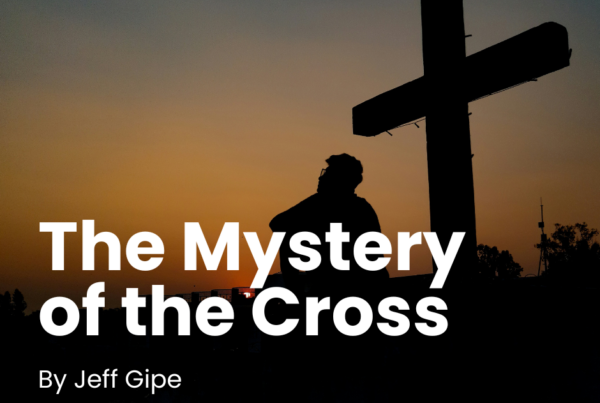

Is it possible that snuggling next to the man or woman of your dreams by a fireplace and drinking hot chocolate is the ultimate aim, and Jesus is just a means of finding that or coping without it?

Since most of us celebrate Christmas, it is important that we dig down into why we do what we do, and ask what values am I reinforcing or negating. For example, is it possible that the celebration of Christmas does not reinforce the meaning of Christ’s birth in the lives of those who celebrate it? Is it possible that consumerism is the ultimate value in a person’s life, and that Jesus just becomes the means of getting what I really want? Is it possible that family is the ultimate good and Jesus is a means that serves the ends of those relationships? Is it possible that snuggling next to the man or woman of your dreams by a fireplace and drinking hot chocolate is the ultimate aim, and Jesus is just a means of finding that or coping without it? Let’s dig a little deeper and find out.

It is well known that the Christmas season can be quite depressing for many people. Perhaps this even includes you or someone close to you. In any case, how do we account for this phenomenon? I want to suggest that the Christmas season, for many of us, functions as a time for evaluation of our deepest desires and sense of fulfillment (or the lack thereof). [Note: I am aware that some suggest that the “holiday blues” has to do with the weather and/or shortened days/time change. While this suggestion may account for some of the reports of people “feeling” depressed, it does not account for the kind of deep existential “thinking” that goes on at the same time]. While most of the year we are functioning in ritual or practice mode, there are key events during the year (birthdays and weddings as well) that cause us to pause and think about liturgies, or the things which ultimately matter and how we relate to those things.

The truth is that we may have idols in our lives. Christmas should be the ideal time to expose them, but many times, it may be idol business as usual. Rather than saying, “Thanks, Jesus, for giving me a family, friends, husband/wife, kids, presents, a tree, weather, hot chocolate, movies,” or “Thank You, Jesus, but I don’t have the things I really want this Christmas,” we should aspire to say “Jesus, You are my greatest gift and greatest desire. Everything else pales in comparison to You. These many good things are only gifts, but You are the giver of every good and perfect gift (James 1:17). Jesus, even if I have nothing, but still have You, then I have everything.” If we choose to celebrate Christmas at all, we should be zealous for God’s glory.

If we are honest, this kind of evaluation means that all of us will probably need to confess some sin. The truth is that even the best of us are capable of making idols out of anything. We should use the Christmas season to allow ourselves to be evaluated by God, instead of evaluating God based on what we have or don’t have.

As we think through these things, we should then move to apply them to our particular traditions at Christmas. You may want to rethink your church attendance, your gift giving and receiving, how you decorate, how you incorporate Scripture and prayer into the Advent season, who you spend Christmas with and who you don’t, where you go and where you don’t go, what thoughts you dwell on and what you don’t. Think about the implicit values of Christmas as you grew up with it, as well as what should they be, ask what the alternate narratives and meanings of Christmas in modern American culture are, and compare and contrast them with the narrative and meaning of the Bible story.

While I certainly don’t want to be the proverbial ‘party-pooper’, I do want to make sure we are clear about whose party it actually is. In fact, this is the gift at the heart of the Christmas story. And here it is, are you ready for it? Christmas is not about you. It is about Christ. The history of the world is one in which all humans try to make saviors out of people and things that cannot save. Christmas is the story that rescues us from the story of idolatry that crushes the human spirit. I love this line from “O Little Town of Bethlehem – The hopes and fears of all the years are met in Thee tonight”. Let your observance of the Christmas season teach you to give both your hopes and your fears as gifts to the babe in the manger, Who came as the Father’s gift to you.

* I borrowed these terms from James K.A. Smith’s book “Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation”. As mentioned above, one may or may not want to adopt his terminology. The value of adopting his terminology is that it opens the eyes to the fact that many of the so-called “irreligious” practices of the world really do function “religiously”. But if those terms are unwelcome ones from past experience, feel free to change them, so long as you understand changing the terms does not change the reality of the concepts that have been described.