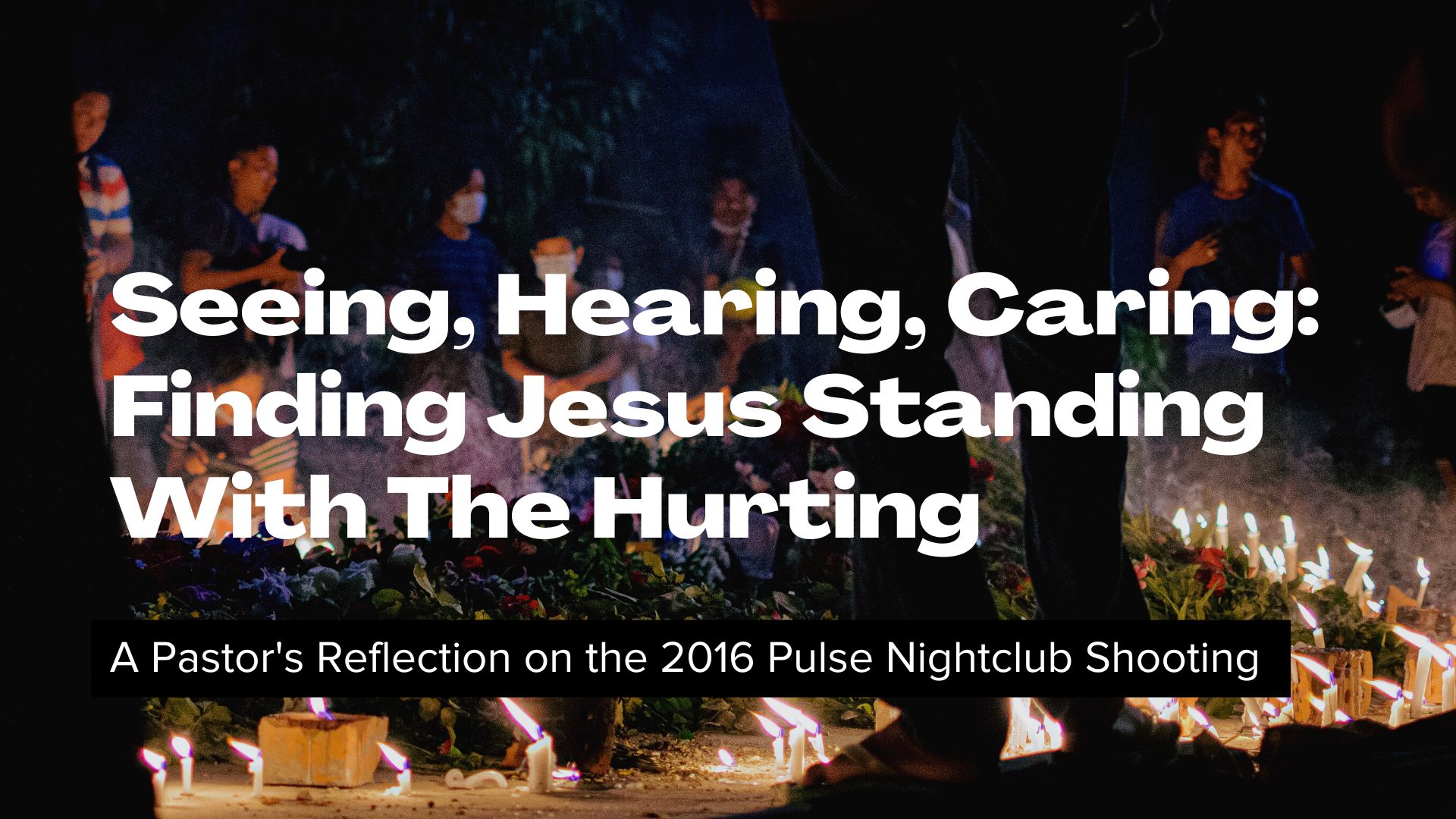

On Sunday morning, June 12, 2016, while on a trip to Seattle for a friend’s wedding, I woke up, grabbed my phone, opened up Facebook and was instantly made aware of the horrible news of another mass shooting in the U.S.

Omar Mateen, a 29-year-old security guard under the influence of radical Islamist ideology, had just killed 49 people and wounded 53 others in a mass shooting inside Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida.

My stomach sank at the news. It was so tragic. I wanted to say something but didn’t know what to say at that moment. My wife and I were running late so we headed out the door, me still processing it all, and soon found ourselves at a little church called “Calvary The Hill.”

Pastor Justin Thomas preached the sermon that morning. At the end of his message, he started talking about the shooting. With compassion and emotion in his voice, he encouraged us to “be the Church” and step into this horrible moment with the victims by devoting ourselves to prayer.

Justin then told us about a vigil for the shooting victims that was happening later that night. He said he would be there and encouraged us all to attend. My wife leaned over and whispered, “I think we should go to that.” I nodded in agreement.

I was thinking this vigil was organized by Calvary The Hill. I envisioned a small group of maybe 10-20 people, standing in a circle holding lit candles, joined in quiet prayer for the victims.

I thought to myself, “What an amazing way for the Church to show the community that we are a light in the darkness!”

I was not prepared for what I saw when we showed up to Cal Anderson Park that evening.

Over 1,000 people had gathered in the park that night to honor the victims, and the entire park was covered with both rainbow flags and flags bearing the symbols of the Muslim faith.

Like I said, I was not prepared.

As a show of solidarity, the vigil had actually been organized by the local LGBTQ and Muslim communities.

Several of these community leaders began to take the stage. The first was a young Muslim woman who spoke passionately. She said, “We are standing here today to tell you that we as Muslims in this community are sickened by what has happened. This is not what true Islam looks like, and we want you to know that we grieve with you and we love you.”

I was taken aback.

In my sheltered, Christian upbringing, I had not really been around many people from these two communities, and of course, in conservative Christian culture, there are so many stereotypes that have become embedded in us about these groups.

This was not what I expected to see. But here it was: LGBTQ people and Muslim people, publicly sharing in grief, honoring one another’s humanity, and standing together during a great tragedy.

And there I was, a Christian in the middle of it all, finding myself in the minority group for one of the first times in my life.

I was amazed at the outpouring of love and support that these two vastly different groups were showing one another.

As I looked at the sea of rainbow and crescent moon flags, for a brief moment, I wondered, “Should I be here?”

I’m ashamed to say I thought this, but I did. As someone who had worked in the Church his entire adult life, and at the time was serving as a youth pastor in a local church, usually when I was a part of a big crowd, it was a crowd of other Christians doing “Christian things” (church camps, worship nights, harvest festivals, and the like).

In addition, I was surrounded by two groups who held radically different ideologies than my own. As a theological conservative who held to the historic Christian sex ethic, and as a participant in a faith that often found itself at odds with Islam, I felt out of place.

Again I wondered, “Is this where I should be?”

Thankfully, the Holy Spirit removed all doubt from my mind by simply saying to my heart in that moment: “Yes, this is exactly where you should be. Because this is where I am.”

The community leaders had just called us to a moment of silence. As my wife and I stood shoulder to shoulder with the people around us, I could see the pain in their eyes, the mourning, the longing for a world without this kind of violence and death.

I was overwhelmed with emotion as I saw tears in the eyes of so many around me.

I bowed my head and began to silently pray for the people around me, that Jesus would comfort them and reveal Himself to them in the middle of their suffering.

I understood what Jesus was telling me.

He cared for these people. He saw their pain. Even though so many there did not know Him, He knew every single one of them. And His heart broke for them. For the victims. For their families and friends. These were people He loved enough to die for.

The Jesus who once wept for Lazarus now stood there with those weeping around me. He was there.

So often in the church world, we think the place to find Jesus is wherever we find the biggest stage, the best music or the most engaging speakers.

But so often we miss that Jesus is present in the places of humanity’s deepest pain. He is the God who cares, and He cares regardless of what flag you’re waving at the time.

Yes, I believe the Gospel must be preached. Yes, I believe people need truth. Yes, repentance is essential to Christ following. All of that is vital, and always will be.

But that was a day I learned about something that was also important to Jesus: allowing myself to be willing to just stand with my fellow humans and love them unconditionally, as Jesus did.

In the age where our conservative tribe seems to agonize over what will or won’t be perceived as “woke,” I firmly believe we need to rediscover the art of simple compassion. We must reclaim our ability to see the humanity in all people, and not only that, but also our ability to show them that the Church cares deeply about all people.

I’m so thankful for this moment, and the leadership of pastor Justin Thomas for encouraging us to take a part in it.

There is a time to simply preach the Gospel, and there is a time to stand next to someone in their pain and simply say, “I see you, I am here, and I care.”

More often than not, it’s the latter that opens people up to hearing the former.