There are acts of unplanned kindness that break through the humdrum of daily existence and shine a new sense of light. Infused with grace, these unexpected gifts have the power to change the course of someone’s day or even become a life moment, an example for generations to come. One such event, described in a BBC documentary1 by those who lived through it, had the power to potentially stop World War I on December 24, 1914.

The Western European propaganda promised both sides that the enemy would be defeated and the troops would be home before Christmas.

It was the end of the “Belle Époque,” a period of prosperity and insouciance. Europe was expanding, a patriotic fervor enflamed it’s citizens, all the while the divide between rich and poor increased. Pictures of the times leading up to the beginnings of hostilities show jovial youth in pristine uniforms with the glimmer of future conquest in their eyes. It would appear that a decisive rapid victory was inevitable—the media promoted it, the governments promised it, and the military high command assured it.2

The reality was quite different. On the Western Front, the German army marched through neutral Belgium and pushed within 70 miles of Paris. The Allied forces exploited a weak point in German lines and brought the battle back up to the Alsace and Lorraine area while a race to the sea drew a new battle line through Belgium. The fighting intensified as the two opposing armies dug down and made trenches that would last the duration of the war.

By December of 1914, the talk of a valiant instant victory was crushed under the news of a horrific death toll due to newer technologies. Testimonies of war crimes streaming from the civilians caught in war zones and villages disappearing under the rubble.3

The Pope attempted to call a cease-fire for the holidays, in hopes to appeal to the Christian heritage on both sides. Word circulated to the troops of the front but neither high command was willing to consider it.

The bitterness of war had already sunk into the heart of the entrenched enemies. Fighting continued to rage until the night of December 24.

Witnesses speak of a light snow fall that night. A profound desperation and chill from living knee deep in mud, fighting to keep their rations from rats as they were huddled to the ground when Christmas time arrived.

That’s when something extraordinary transpired that has never been repeated, at least not in the same way, nor on the same scale.

In the north by Ypres that night, the British soldiers listened as the shelling was replaced by a chorus of “O Tannenbaum” The unexpected beauty was remarkable enough for them to answer with “The First Noel,” and then the two opposing armies joined together singing, “O Come All Ye Faithful.”4

In France to the south, the French army hushed to sound of the Germans singing “Silent Night.” Not be out done, they joined in, each army singing in their respective languages.5 In some places the Great War raged on, but all over the Western Front, a spontaneous movement of peace was observed as the troops celebrated together the Savior’s birth, even if from the inside of their trenches.

None would have been surprised by a return to hostilities the next day. In fact, that was the case for many that Christmas Day. The high command on either side would not approve of the nights impromptu vigil. Yet, in a day without the instant communication technologies that would later help control armies, there was a little more leeway to be human.

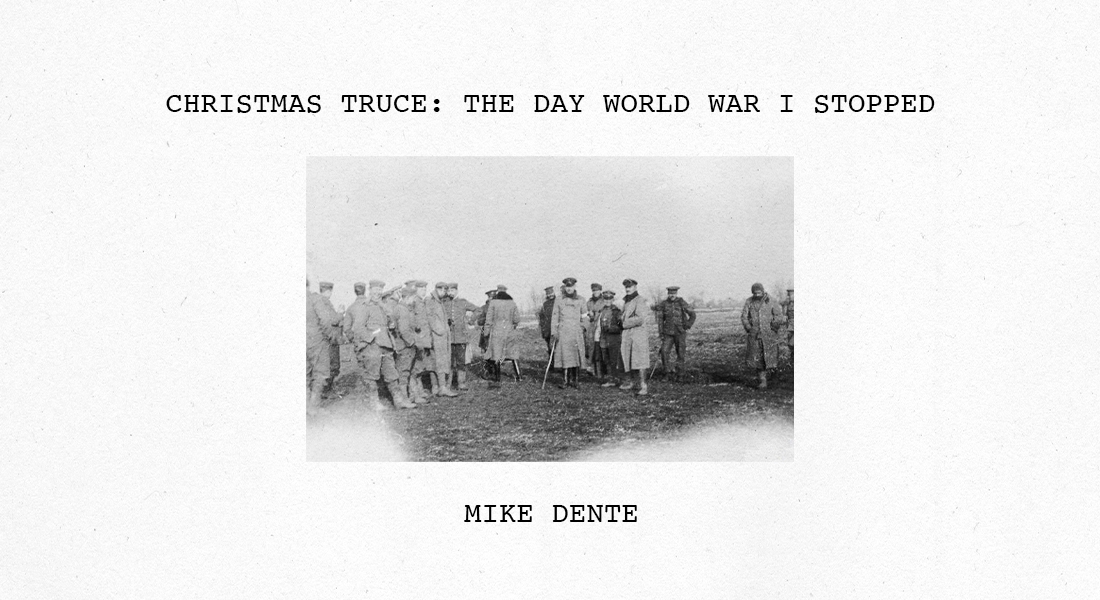

That day the Germans put up small Christmas trees on their trenches. Surprised English soldiers took pictures that can be found today by a simple Google search. But the goodwill didn’t stop there.

Numerous witnesses speak of the unimaginable.

Germans stepping out of the trenches with white flags, meeting the enemy in the middle, in No Man’s Land. They didn’t come to fight. They shook the hands of the enemy. They arranged for the dead to be buried. They held Christmas services.

The fraternizing went further. Enemies spoke of families waiting back home, exchanged Cognac, Cigars, Chocolat and other delicacies. There were football matches documented by photographs sent home in many of the amazed soldiers letters. In some places the unofficial truce lasted until the New Year.6

When the authorities on both sides heard about the Christmas Truce, they were furious. The news reaching home was limited to the best of their abilities. The propaganda machines needed to turn and keep the public approval of the war effort. Photographs and letters were destroyed. A warning was issued to soldiers on both sides that further fraternization with the enemy would end in charges of treason. Both sides doubled efforts the following years to ensure that it never happened again.7

It stands to wonder what would have happened if the movement spread.

What if reason returned, and the peace of Christ incarnating into our world transformed into more than just a truce? Christmas is a time when many seek peace, but not everyone finds it. Statistics today speak of depression, suicide and overwhelming debt. But what if there could be peace? It’s enough to make me think of the conflicts within our movement and in our personal relationships. I wonder if the Gospel might not be applied to bring peace to our lives as we put down our arms, our comebacks, our pride, as we stop for a moment to remember the One who became a man to take away our sin. Our High Command, however, won’t ask us to pick up our guns the next day. I wonder if He might not even ask us to do more than agree to a Christmas Truce. Chances are, He’d call us to live in His peace.

Image above credited to Imperial War Museum.

1 Peace in No Man’s Land, BBC

2 Apocalypse la 1ere Guerre mondiale, Furie

3 Verdun Memorial

4 The Smithsonian Magazine

5 Verdun Memorial

6 France 24

7 BBC iWonder