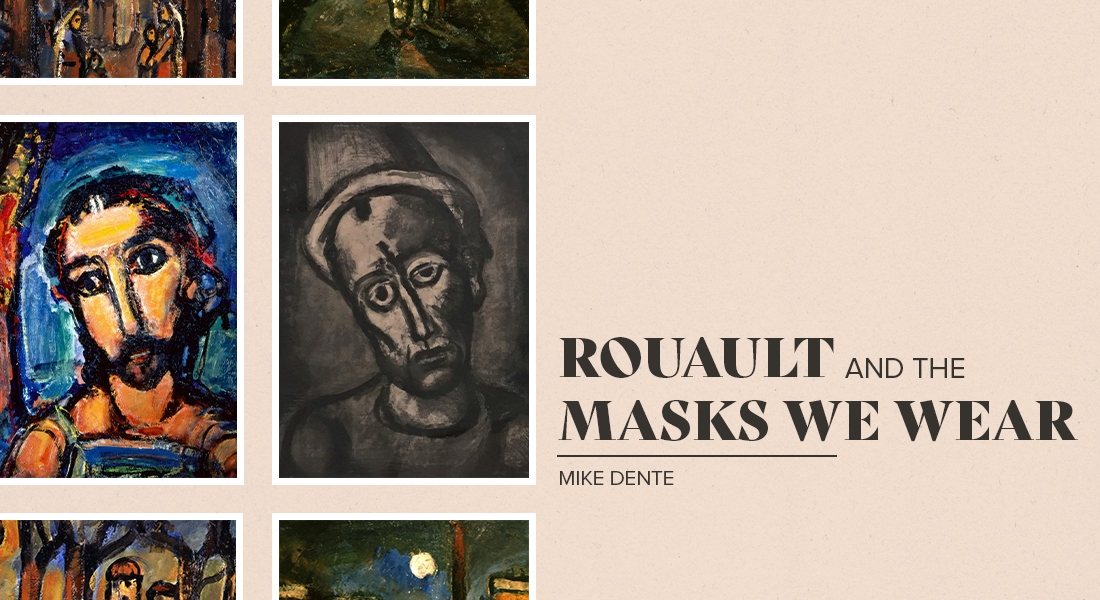

From time to time, a work of art can touch our soul. It examines us and provides a filter like a camera’s focused perspective. In this way, art captures a feeling or a truth, and makes it more relevant to our existence, as it invades our imagination. That’s the effect Georges Rouault’s paintings had on me when I discovered them. Who is this artist? How does his work speak today? First, I would like to present the man and his art, and then I’d like to take an apologetic look into one of the themes that moves me: the masks we wear. In this way, I hope to discuss what we hide from others, or even what we show, by talking about social media, lust, and eventually, resting in Jesus.

The Artist

Georges Rouault was born in 1871. His love for art came from his maternal grandfather and in 1890, he entered the Ecole des Beaux-Arts where he became a pupil of Gustave Moreau.1

More than a professor, Moreau was Rouault’s spiritual and artistic guide. In 1895, when Rouault’s work was vetoed at the Prix de Rome, Moreau advised him to leave the academy to paint independently. Later, Moreau wrote to him: “You like a serious art, sober and, in its essence, religious, and all that you do will be marked with this seal.”

After his mentor’s death, Georges Rouault turned toward a spirituality that transfused his work. At the Abbey of Ligugé, he joined a group of artists to create art sacré of such quality that it avoided superficial tendencies. An example of this period is “Madame X: J’irai droit au ciel, disait- elle avec une assurance douce et ferme” (Madame X: I will go straight to heaven, she said with gentle and firm assurance).2 Rouault captures the lady’s austerity, her prayer-shaped hands under a judgmental glare.

As Rouault confided to Édouard Schuré: “I have the fault, (perhaps fault… in any case, it is an abyss of suffering for me…) of never leaving anyone’s spangled coat be he, king or emperor. The man I have in front of me, it is his soul that I want to see… and the bigger he is, the more he is humanly glorified, and the more I fear for his soul…”3

Rouault seemed to live in a struggle with faith and doubt. He survived two World Wars, experienced the joy of friendship and partnership that ended in seeing his works burned by bailiffs over an inheritance discrepancy.4 Rouault knew the depths of human depravity, and yet, he still believed. Writing to Father Regamey, he explained that “art is an ardent prayer.”5

While his work is not limited to religious art, it pushed back the traditional boundaries, as in “Le vieux roi” (The Old King),6 the wealth of Solomon is portrayed in vivid colors, holding a flower, his face is grimaced with exhaustion. In this, Georges Rouault paints the reality that only a believer can see: the multidimensionality of a fallen world. But these sober subjects also give place to gleams of grace like the engraving, “C’est par ses meurtrissures que nous sommes guéris” (By His Stripes, We Are Healed).7

The Parallel to Today’s Age

But to link Rouault’s work to our day, I’d like to turn to the clowns he painted. Why clowns? In “Qui ne se grime pas ?” (Who Doesn’t Wear Makeup ?),8 we have an answer in the suffering of a man who barely tries to hide his pain, and whose provocative question denounces us all.

Rouault tells us through his letter to Schuré where the inspiration comes from:

“This nomad’s carriage stopped on the road, the old stalwart horse that grazes the thin grass, the old clown sitting at the corner of his trailer mending his shiny and variegated coat, this contrast of shiny, scintillating things made for having fun and this life of infinite sadness… I saw clearly that the ‘Clown’ was me, it was us… almost all of us…”

Effectively, we all wear masks. We all at times draw attention to the center of what we want to show and hide what gnaws at the soul. Herein is our apologetic relevance, and by apologetic, I take Yannick Imbert’s definition: “The demonstration in words and in deeds of the Christian worldview or philosophy over and against all forms of non-Christian worldview or philosophies.”

Wearing a mask is nothing new, but Rouault exposed a human flaw. What are the masks of our day? The types of masks that mark our times can be synthetic like social media, which is used as a projection of who we want to be and what we choose to show to the world. The mask becomes a post, a picture, a live feed or even a comment. The moment we enter the stage of the public world, we send a message that highlights something we wish to show. There is an effervescent community essence to it when all goes well. It feels good to receive accolades, to share a moment, and there is comfort in aligning ourselves with others who have similar interests.

But in the worst cases, these same internet masks can become harmful like cyber bullying or promulgating false information. Though I’m talking about our social networks like Facebook, Instagram, etc., I am in no way campaigning against them. They are just a conduit for communication, but one that reveals deeper issues brought up by Rouault like the spiritual condition of the human heart. One example is the constant comparison to others that can induce “a state of desire to have more than what is due, give rise to instability, greed,”9 or simply put— lust. According to Colossians 3:5 and Ephesians 5:5, the apostle Paul denounced lust as idolatry.

The Link Between Artist and Masks

What’s the link? To paraphrase Calvin in his commentary on Ephesians, it’s “replacing God with a greater desire.” The representation, which becomes our main desire to maintain, ends up being our mask. When we speak of masks, we come to hypocrisy (behind the word is the definition, “wearing a mask”), whereas Jesus invites us to transparency and to draw near to God. He asks that we lower our masks, lay down our pretensions, and come to him, even in suffering, to find peace (Matthew 11:28-30).

When we pray through a mask, be it the mask of supposed spirituality, false humility, or even expertise in theology, we are not being honest with God. This unnecessary effort drains the grace we so desperately need. In wearing the mask, we are proving our merit or shielding our hearts from the Lord’s sanctifying work. After all, only the sick need a doctor. But when we let go, especially in the suffering that comes from recognising the ugliness of our sin, we receive the peace of forgiveness from our Redeemer.

His rest will lead us to healthy prayer, not to mention a better use of social networks. No longer an idol, we can avoid being eaten up by lust. Even if the masks are part of social media, we don’t have to give ourselves entirely to the game. No one puts an ugly profile picture unless it’s done on purpose. My current profile picture is the most staged picture I’ve posted, but I kind of like it.

Honestly, we shouldn’t take our masks too seriously, nor those of others. There is a balance that we all must strike between not wearing our feelings on our sleeve and being comfortable with ourselves, mask and all. Moreover, we cannot escape our humanity, and that is not what Christ is asking for. The Christian is called to put on the new humanity in Christ (Romans 13:14), and thus, we will find rest for our soul and transparency towards others that comes from being justified. In this, Georges Rouault’s paintings show that, though we all might wear an occasional mask, through resting in the Lord, we can escape the trap of feeding into duplicity.

Images of Rouault’s paintings in the graphic above credited to the following:

Notes:

1 For most of the biographical information I followed the website for “La Fondation Georges Rouault.”

2 “Madame X.”

3 Taken from a letter from Georges Rouault à Édouard Schuré on Sunday, 10 juin 1904. I owe this and other quotes from the help of the artist’s granddaughter Mme Anne-Marie Agulon.

4 “La fuite en Égypte huile sur papier marouflé sur toile, vers 1946 Paris, musée national d’art moderne, centre Georges-Pompidou”

5 “If art is sometimes an ardent prayer if I do not blaspheme by saying it too loudly, it will be my consolation if some of my works sometimes bear the imprint of it or highlight it, fortunately.” I also owe this quote to Mme Anne-Marie Agulon

6 “Le vieux roi, 1937.”

7“C’est par ses meurtrissures que nous sommes guéris.”

8 “Qui ne se grime pas ?”

9 Definition taken from the Lexicon BDAG of the Greek word : πλεονεξία (covetousness )