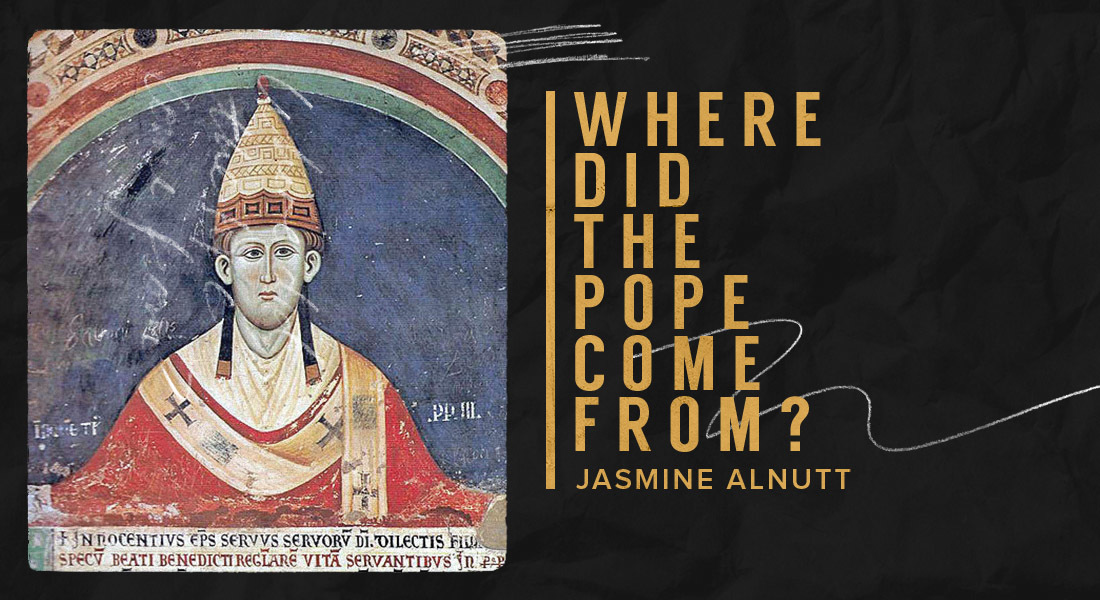

Where did the Pope come from? How did he become so important? These are questions many people ask today. While the history of the Papacy in Rome is long and complex, as with most things it did not start out that way.

In a previous article we saw that, as society transformed under Emperor Constantine and his successors, the Church, led by its bishops, became a prominent social and religious institution throughout the Roman Empire. Over the next two centuries, circumstances developed that would give the Church political influence as well.

This is seen most clearly in the evolution of the office of the Bishop of Rome.

Although some of Rome’s political influence diminished when Constantine moved the center of the Empire to Constantinople, the Eternal City never fully lost its religious force. Rome was always held in high esteem among the churches due to its size, resources and good works; so since Rome’s church was important, Rome’s Bishop naturally held a prominent role among church leaders. In fact, throughout the fourth and fifth centuries, this role began to expand.

At the Council of Constantinople in 381 A.D., Emperor Theodosius boldly pronounced Constantinople the seat of religious as well as political authority. Damasus, the Bishop of Rome, protested that church influence should not be based on political influence; just because the city of Constantinople now held political preeminence, it did not mean that its Church should have equal power by default.

Rather, Damasus argued a supposedly more “spiritual” premise to determine church primacy—the “Petrine Theory.” This theory claimed that Jesus gave authority to the Apostle Peter when He said in Matthew 16:18-19, “On this rock I will build my church…. And I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven.” Because Peter ministered in Rome and was martyred there, this authority was then passed down to the Bishop of Rome and his descendants; therefore, Rome’s Bishop deserved preeminence among the churches. It is likely that Damasus’ claim originated with second century church father Irenaeus, who referred to “…the very great, the very ancient, and universally known Church founded and organized at Rome by the two most glorious apostles, Peter and Paul….It is a matter of necessity that every church should agree with this church on account of its preeminent authority.”1

A misguided Theodosius concurred with Damasus’ claim, and in the Edict of Thessalonica he upheld the authority of the Roman Church, thereby validating the Petrine Theory. For centuries to come, this specious notion was employed liberally by the Roman Church as the power struggle between Rome and Constantinople continued over the years.

In hindsight, it seems clear that the Petrine Theory was a spiritual cloak for fleshly, political motives.

Ultimately, Damasus wanted to make sure the Roman Church stayed predominant. This wasn’t about the glory of God; it was about the glory of the Roman Church! Perhaps Damasus would have been well advised to consider the Apostle John’s rebuke of those who “like to have the preeminence among them” (3 John 9). And yet because of this turn of events, Rome did indeed continue to grow in preeminence. For example, in 401 A.D. Innocent I made a rule that no important decisions could be made by the western churches without the consent of the Bishop of Rome!

As the Roman Bishop established spiritual authority, he would soon have opportunity to claim political authority as well. Surprisingly, this came about as a result of a series of invasions of Rome beginning in 410 A.D. Although they signified the demise of the Western Empire, these attacks gave opportunity for a new leader to rise from the midst of the chaos and unite the religious and political power of the Roman Church into one figurehead—Leo I, the man who truly defined the role of the Roman Papacy. As Shelley states, Leo “provided for the first time the Biblical and theological bases of the papal claim. That is why it is misleading to speak of the papacy before his time.”2

Leo was a proud and influential nobleman who spoke out vehemently against heresy and was considered a strong defender of the faith. However, Leo also enjoyed power and control. He aggressively asserted Rome’s influence based on the arguments of the Petrine Theory. Bennett notes, “Leo believed Peter and Paul had been sent to Rome so that the knowledge of God could radiate from…the center of the civilized world.”3 He began to lay an authoritative foundation for his office, and in 445 A.D. he declared his supremacy as the leader of Christendom, stating, “As the primacy of the apostolic see is based on the title of the blessed Peter, no illicit steps may be taken against this see to usurp its authority.” From there, he took advantage of the unstable political atmosphere to extend his leadership.

In 452 A.D. Attila the Hun attacked an already vulnerable Western Empire. As he marched on Rome, Leo went out to meet him and convinced him to withdraw his position, for which Rome’s citizens were profoundly grateful. Yet three years later, Gaiseric the Vandal marched on Rome. The Romans panicked and murdered the Emperor, so once again Leo stepped in and convinced Gaiseric to withdraw after looting the city. These events catapulted Leo to the status of hero in Rome. The Romans were thankful and proud of their “Papa” or “Pope,” a familiar Latin term meaning “daddy.” Indeed, they began to view him not just as a spiritual father, but political as well. Therefore it is not surprising that “Leo’s leadership in these political crises helped begin the long process by which the Bishop of Rome became the most powerful Western figure in the Middle Ages.”4

We know this figure today as the Pope.

From humble beginnings, good works and rapid church growth emerged an intricate system of politics and religion still active in the twenty-first century known as the Roman Catholic Church, headed by it’s official leader, the Pope. What began as a simple position of service developed into a powerful, authoritative office whose influence extended throughout the world. The development of this complex institution is itself a commentary on the challenge of maintaining simplicity as the Body of Christ. No wonder Paul warned the Corinthians not to be “corrupted from the simplicity that is in Christ” (2 Corinthians 11:3, NKJV). It is in the simplicity of the Gospel message, not a religious office or political position, that we find “the power of God to salvation for everyone who believes” (Romans 1:16, NKJV).

Notes:

1 Irenaeus, Against Heresies 3.3. Although Irenaeus claimed that Peter and Paul founded the Roman Church, other historians believe it was founded by unknown Christians (see Church History in Plain Language by Shelley, p. 31 and A History of Christianity by Latourette, p. 66). This seems most consistent with Scripture, as Paul wrote in Romans 1:8 that the Roman Church’s faith was already being “spoken of throughout the whole world” before his arrival.

2 Bruce Shelley, Church History in Plain Language

3 William Bennett, Tried by Fire: The Story of Christianity’s First Thousand Years

4 Mark Galli and Ted Olsen, 131 Christians Everyone Should Know